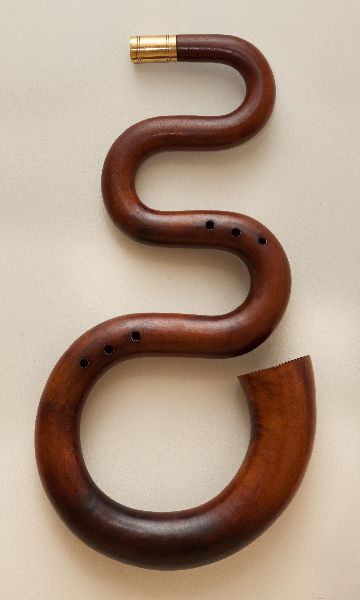

End XVIth c. – 1590. A writing from the 18th century attributes the paternity of the serpent, known as « church serpent » and in its proportions to a canon from Auxerre, France, named Edmé Guillaume. This document is the only one to attest that filiation. Yet we find in the same period on the italian side of the Alps quite similar instruments that might have inspired Canon Guillaume or other people.

XVIIth c. The serpent is very present in the iconography and already pictured under its present form. We find contracts of employment for serpentists in a lot of religious institutions like Notre-Dame des Doms in Avignon (1602), Saint-Agricol d’Avignon (1613), Saint-Nazaire de Béziers (1627), Troyes (1643), Sainte-Chapelle de Paris (1651), Chartres (1655)…

Its principal function is the accompaniment during plainsong services among the singers or in the continuo of the church instrumental ensembles.

The serpent is officially taught to cantors in the Royal Chapel of Versailles in 1664.

XVIIIth c. While military campains sweep Europe around 1700, orchestras meet and influence eachother. They also become more structured and entrust the bass to the serpent, the then only wind bass available next to the bassoon and bass trombone. We find it for example in the Gardes Françaises (France, 1765), the Hanoverian Band (United Kingdom, 1785)…

With this new use, the instrument evolves technically ; it lengthens for more ergonomics and sound projection and receives keys for more stability when playing forte.

Its teaching continues after the french revolution in the Conservatoire of Paris with the aim of providing serpentists to the rising number of harmony orchestras (military and republican), but also to increase its use in church.

It then enters the orchestra always next to bassoons and is heard in works such as Royal Fireworks (Händel, 1749), Divertimento St. Antoni (Haydn, circa 1780), March for the Prince of Wales (Haydn, 1792)…

XIXth c. A strange mix is to be noted between the will to make evolve the manufacturing of the serpent on one side, to promote its teaching, and virulent speeches from famous musicians like Berlioz to make it « disappear », while he continues to write ochestral parts for it.

As a matter of fact, the role of the serpent is going to decrease progressively in an always growing romantic orchestra where the race for volume and bass runs beyond the limits of the instrument. The serpent evolves, transforms in an attempt to follow this evolution (more keys, form, brass instead of wood) and becomes the ophicleide (from the greek « key serpent »). But the race for bass continues and the arrival of the dubble bass tuba with all the saxhorns family make the ophicleide step aside.

In spite of all, the serpent and the ophicleide remain surprisingly present in some parishes until the end of the century.

XXth c. – 1970. The serpent is born again in England thanks to the enthusiasm of Christopher Monk who builds then his own instruments. His work to make the instrument welcome is huge ; he founds the legendary and eccentric « London Serpent trio ».

Some years later on the other side of the Channel, Bernard Fourtet, ancient instruments specialist, and Michel Godard, jazz musician, give the impulse to a new approach of the instrument, both in terms of sound and opening to new musical repertoires. They initiate trainings and give birth to a new generation of young serpentists.

After a century break, the serpent then takes its seat back among baroque and pre-romantic ensembles and steps towards contemporary music, supported by a demanding instrumental manufacturing.